ALL ABOUT FORMULA 1

REVIEWS OF ALL SEASONS

LANGUAGE

THE ART OF SETTING UP AN F1

Setting up a Formula 1 car is an extremely complex task, as there are thousands of different setup combinations. It's not just speed that matters, but the consistency of speed throughout the race with different types of tires. No matter how good the car is, it's always necessary to optimize its performance for each track of the season.

For this reason, the driver's work with the engineers and the analysis of telemetry is fundamental. According to Christian Horner, former Director at Red Bull, there are 15,000 data points to be analyzed by telemetry, so the driver who understands how CAR SETUP works will have an advantage over the others.

The Formula Brumnh Channel made a very interesting video explaining some car setup adjustments using the steering wheel buttons. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yFCIDsGZgyU&t=909s

THE EVOLUTION OF THE SET UP

n the 50s and 60s, car setup was limited to mechanical adjustments: engine, gearbox, suspension, ride height and tires. Fangio, for example, would talk to his chief mechanic and ask for modifications to the car's settings.

Starting in 1968, F1 entered a NEW ERA with the introduction of aerofoils and the arrival of slick tires in 1971. During this period, aerodynamic tuning became increasingly important, and tuning possibilities increased. The driver became a key player in providing information about the car, as there was no telemetry. It is no coincidence that the drivers who were good at accuracy (Stewart, Fittipaldi and Lauda) outperformed the drivers who were not good at accuracy.

In the early 1980s, telemetry emerged in F1, providing information that was available to drivers and engineers to adjust the car for each type of circuit. Drivers like Piquet, Prost, and Lauda were already excellent track recorders and took full advantage of this technology, winning seven titles during this period. Senna himself, a skilled engine developer, also made extensive use of telemetry.

In 1992, with the emergence of the Williams FW 14B, onboard electronics became the dominant factor in the car's setup and handling, as the DRIVE AIDS altered the car's height and center of gravity, controlled tire slippage and gear changes, and this made driving a Damon Hill almost like driving an Alain Prost, which was definitely not true. For this reason, the FIA had to ban most electronic devices for 1994.

In the 2000s, two-way telemetry emerged, allowing teams to adjust car settings directly from the pit lane. However, in 2003, it was banned from F1. As a result, setup changes during races were made by the driver using controls on the car's steering wheel. Schumacher took full advantage of this technology.

These days, the driver no longer sets the car, 90% of the tuning is done by the team's engineers. At most, the driver tweaks the setup with the steering wheel controls, and even then, with guidance from his engineer.

On this page of the website we will give a small sample of what it's like to tune an F1 car. Below is a photo of the numerous controls on the steering wheel of an F1 car (Sauber 2015).

1) ENGINE AND ENERGY RECOVERY SYSTEMS:

The engine is perhaps the most important part of an F1 car; the entire aerodynamic design is based on it. It is estimated that every 10 HP increase in engine power represents approximately 0.2 seconds of lap time, depending on the type and size of the track.

In the 1980s, there were special super-powerful training engines that lasted only 2 or 3 laps, and in races, engines were designed for reliability and fuel economy. At that time, telemetry was in its infancy and engine development was impossible without feedback from drivers.

From 1984 to 1988, the regulations gradually reduced the amount of fuel in the tanks, forcing drivers to reduce boost pressure and adjust the fuel mixture during races. Since there were no multiple engine maps like there are today, it was not uncommon for engines to break down due to these changes.

Senna was an expert in this area, he provided information on where the engine could be improved and was fundamental to the development of the Renault and Honda engines.

“Especially for the team, which was important to us, so this was the way he guided us in the development of things regarding the engine. In other words, he (Senna) made choices, and we realized that he never made mistakes, he guided himself perfectly. He was very guided by instinct, which was so correct that I trusted him.”

(Mauro Mauduit - Renault Engineer)

"He (Senna) was very good at development, working on the engine... he would made a lot of changes to the engine setup, then you could relate your lap times to fuel economy ratings and all sorts of information right out of your head..."

(Steve Nichols - Former McLaren Engineer - Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jNhNmDwr7j4&t=21s)

The current F1 car has several types of engine mapping, each with different power transfer response modes. One can choose a more aggressive mapping for qualifying, a slightly less aggressive one for races, a soft one for low-grip track conditions, or a very soft one for wet track conditions. Each mapping choice depends on the track's grip conditions.

In the current turbo era (2014-2025), energy recuperators called MGU-K and MGU-H were implemented.

The MGU-K is powered by heat from the braking system to transfer rotational energy to the crankshaft, and the MGU-H is powered by heat from the turbo to transfer rotational energy to the turbo shaft to prevent turbo lag. These systems can be used in sections of the track where the team believes they are most important. All of this makes F1 much more complex.

2) GEARBOX:

The gear ratio is essential to keep the engine operating within the maximum torque and power range throughout the race. Nowadays, engine manufacturers already have a gearbox with the ideal ratio for all tracks, and due to the regulations it is mandatory to use a single gear ratio for the entire season.

But in F1 in the past, this relationship was established empirically. It was common for engineers to ask drivers if, at the end of the fastest straight on the circuit, the rev counter needle reached the red line. If this line was reached, the engineer could choose a longer ratio for the last gear.

In the 70s and 80s, on the most difficult tracks (Monaco and Detroit), the driver could ask to exclude the highest gear if it was not being used, to have one less gear and reduce the weight of the car.

After the 90s, with semi-automatic transmissions and the development of telemetry, it became easier and today it is the engineers who establish the ideal gear ratio for the tracks. Another adjustment that exists in current F1 is the engine braking adjustment, which helps the car brake when approaching corners.

3) DIFFERENTIAL:

Differential setup is important on tight tracks with closed corners. Contrary to what many think, in low-speed corners you don't gain time by pushing the car to its apex, but rather by regaining speed. A looser differential allows the rear to rotate faster and, theoretically, you can accelerate sooner.

The Williams FW 14B had an electronic differential programmed for each type of corner, giving the Williams car a significant advantage, but in 1994 onboard electronics were banned by FIA regulations.

Currently, the differential is one of the adjustments the driver can make on the car's steering wheel, and it's such an important adjustment that there are 3 different differential settings for corner entry, mid-corner, and corner exit.

4) WEIGHT DISTRIBUTION:

Weight is everything in this sport. It is estimated that every 10 kg increase in the car's weight represents an average of 0.3 seconds per lap, depending on the size and type of track.

In some situations, the car has the correct aerodynamic and suspension configuration, but presents a slightly front or rear behavior. In these cases, the distribution of ballast in the car can be changed to correct this unwanted behavior.

This was the case with Williams 2003, which began the year with understeer behavior, and from the Monaco GP onwards the team replaced the carbon fiber nose with a steel nose weighing 12 kg, which improved the car's handling and made it competitive enough to compete against Ferrari. (Source: AUTOMOTOR Yearbook 2003 pg 101 and 124)

5) SUSPENSION SETTING:

Suspension setup works in conjunction with the tires and is crucial to the car's cornering behavior. However, external variables such as asphalt abrasion and grip, track temperature, and even whether the car has to drive over curbs influence the choice of suspension type.

An excessively stiff suspension helps keep the undercarriage parallel to the ground in corners, increasing speed at the apex of the curves. Conversely, depending on the track, it can cause the car to lose traction on corner exits and tends to wear the tires faster. Another interesting point is that if the front suspension is extremely stiff, the car's dynamic movement will be limited, and the car may have difficulty entering corners.

A softer suspension allows for greater weight transfer during cornering and braking, increasing the car's dynamic movement, but losing some stability at the apex of corners. On the other hand, this type of suspension tends to wear the tires less and improves traction when exiting corners. Generally, on undulating tracks, a slightly softer suspension is used.

To complement the suspension setup, there are various types of shock absorbers that generate different behaviors in the car, and this further increases the range of different set-ups.

Another adjustment is the in-car stabilizer bar, which was invented by Colin Chapman. This device allows the driver to adjust the stiffness of the stabilizer bar to control the car's lateral tilt in corners. This adjustment can lessen the effects of "front-end slide," "rear-end slide," or even "all-wheel drive" in the car.

6) WHEEL CAMBER:

It is also possible to change the camber of the front wheels.

Negative camber increases the contact patch of the car's front tires in high-speed corners and reduces tire-to-pavement friction on straightaways. On the other hand, it increases wear on the tire's inner "shoulder," potentially causing its structure to collapse. This is why tire manufacturers limit the maximum camber angle that can be used.

7) TIRES AND THEIR COMPLEXITIES:

In the 50s and 60s, tires were grooved, and it is known that some teams used a set of tires in 2 or 3 races in a row. But from 1971 onwards, with the introduction of slick tires, everything changed in F1. The performance of the tires with the car's suspension setup became a fundamental element in the car's performance.

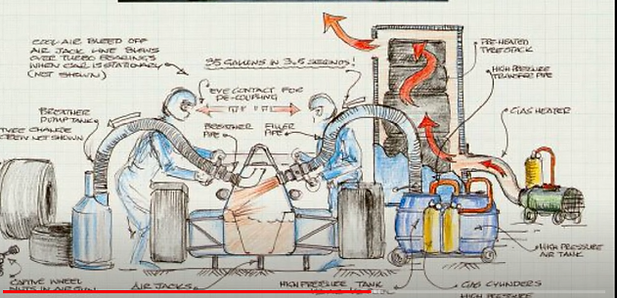

Jackie Stewart was one of the first to realize the importance of tires in modern F1, and created the TIRE TEST that was widely used in F1 in the following decades. Nelson Piquet invented a method of heating tires in F3, brought the idea to F1, and Gordon Murray created a heated cabinet with hot gases to heat the tires. But it was only in 1984 that Lotus upgraded Piquet and Murray's idea and invented the electric tire blanket. See below Gordon Murray's explanatory drawing of Brabham's tire heating cabinet.

Image reproduced from the video on Canal Automobilismo Brasil. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0U4NPrxTT4A at 21 minutes.

Piquet and Senna were very good at understanding the behavior and developing tires. The information we have about Senna is that while the other drivers were concerned with grip and durability, the Brazilian went beyond that and also worried about the deformation of the tire's sidewall.

“In four days of testing I learned more from this guy (Senna) than I learned in the whole year from the other driver.” (Mezzoanotti - Pirelli tire engineer during tire testing in Brazil in 1984)

"Ayrton was in another world and you had to understand that when you talked to him. At the same time, he was extremely boring and meticulous with every detail – driving all the technicians crazy." (Pierre Dupasquier - Engineer and former Michelin Racing Director)

From 1998 to 2008, grooved tires returned to F1 because the FIA wanted to reduce the speed of the cars in the corners. But a different behavior occurred when the tires became worn; they practically transformed into slick tires due to the increased contact surface with the ground, giving the tire's grip a "second life."

After Pirelli's return to F1 in 2011 as the sole supplier, understanding tire behavior became of paramount importance to the success of an F1 car. This is why Pirelli, at the request of the FIA, purposely built its compound in a very narrow "window" of performance-optimizing temperature, as we will see below.

Image reproduced on Pirelli's official F1 website

Below is the tire optimization temperature table, image reproduced from CANAL Fórmula Brumnh.

The table above, reproduced from the Formula Brumnh Channel, demonstrates how difficult it is to set up the car for a different temperature range to optimize tire performance. The ideal temperatures for each tire type are shown in green:

-

Hard tire C1 (ideal temperature 105°C)

-

Hard tire C2 (ideal temperature 95°C)

-

Medium tire C3 (ideal temperature 85°C to 95°C)

-

Soft tire C4 (ideal temperature 85°C)

-

Soft tire C5 (ideal temperature 75°C to 85°C)

-

Intermediate tires (ideal temperature 65°C)

-

Extreme rain tires (ideal temperature 55°C)

From this table, we can see how things are quite paradoxical and complex.

Hard tires require more aggressive driving to reach the ideal temperature, while soft tires require more smoothness. Since hard tires are theoretically used in longer stints, the driver cannot be too aggressive at the risk of losing performance at the end of the stint, which is how complex the situation is.

Tire performance also depends on suspension adjustment, and there is currently no suspension that is ideal for diametrically opposed tires such as HARD and SOFT. For this reason, the engineer uses a setup that suits both types of tires. To complicate matters, the temperature and rubber content of the track also influence tire performance.

Another thing that goes against logic is that hard tires do not always wear more slowly than softer tires. Around 2003 to 2005, Michelin discovered that hard tires caused "micro-slips" that were imperceptible to the naked eye, and in these cases, HARD tires wore more than SOFT tires in the same number of laps.

8) AERODYNAMIC SETUP:

Aerodynamic setup is linked to suspension setup and tire selection. The three elements work together.

Nowadays, all teams know, through computer simulations, what the angle of the rear wing should be for each track during the season. In the past, the driver would talk to the engineer to decide the angle of the car's wings.

There are other alternative options, such as using a setup with more downforce, to have more speed in corners and improve the car's handling. And you can opt for a setup with less downforce, to have more straight-line speed to be able to attack your opponents at the end of the straights, or even to defend yourself from overtaking by your opponents.

In races in the rain, all teams choose to reduce the angle of the front wing, to make the car slightly forward, since an understeer on a wet track is much easier to correct than an understeer.

Another important piece of information is that aerodynamic pressure is proportional to the square of speed, so on tracks with high-speed corners like Spa, Suzuka and Barcelona, downforce will make more of a difference than on street tracks with low-speed corners like Monaco or Baku.

We should also mention that the F1 cars of the 2020s are very refined aerodynamically. There are several aerodynamic tricks such as vortices on the sides of the floor to "shield" the bottom of the car, or the UP WASH effect created to generate turbulence on the car behind. So these cars are very sensitive to any change in setup.

The most important parameter for generating downforce in cars with GROUND EFFECT is the floor, and all other car adjustments are based on it. It should be noted that if the floor generates excessive downforce, the car may suffer from "porpoising" and become difficult to drive. If it generates too little downforce, it may cause a lack of temperature and grip in the tires, impairing the car's performance.

9) CAR HEIGHT FROM GROUND:

Since 1950, the height of cars has been lowering over time, as the goal has always been to lower their Center of Gravity. Steve Nichols (Former McLaren and Ferrari Engineer) said in an interview that every 1 cm less in the car's Center of Gravity can bring gains of an average of 0.3s faster per lap. Of course, this depends on the size of the track.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xRtjeWsIscc&t=2506s (minutes 46/47)

One of the secrets of the 1988 McLaren/Honda (MP 4/4) was the position in which the engine and gearbox were mounted, being 2.5 cm lower than the Lotus/Honda of the same year. (Source: Francisco Santos Yearbook 1988 pg 20)

For cars with GROUND EFFECT, the height of the car is essential to optimize the desired downforce. There is a right height for each type of project, if the Engineer misses the height of the car by a mere 5 mm, the effectiveness of the Ground Effect may be compromised, the car may suffer from "porpoising" or may have problems with lack of grip, or even premature tire wear. Some engineers say that every 1 mm error in the height of the floor in relation to the ground represents a loss of 0.1 seconds in the car's time.

In races with rain, the car's ride height should be slightly increased relative to the ground to improve the flow of water underneath the car, without the water spray creating turbulence in the air passing beneath the car.

10) BRAKE DISTRIBUTION PER AXLE:

In British Formula 3, Nelson Piquet invented a way to bring the brake fluid lines inside the car to adjust the braking distribution. When he arrived in Formula 1, he brought this idea to the Brabham team, which then adopted this technique in its car.

Axle-based braking distribution serves to improve the car's braking performance and control tire wear, as the driver can make this adjustment during the race. In the case of rain during the race, changing the braking distribution is extremely important to improve the car's braking performance.

In current F1, the tire usage "window" is critical to the cars' performance, so it is essential to adjust the brake distribution to better manage tire temperatures. It is no coincidence that engineers instruct drivers about this adjustment during races.

BEST F1 CAR SETTERS:

From what I have read and watched in several interviews with engineers who have worked in several F1 teams (Ferrari, Williams, McLaren, Brabham, Tyrrell, Lotus, Benetton, etc.), these are the best car tuners in history due to their ability to understand the car, communicate the car's behavior to the engineers and make the right setup choices:

-

Nelson Piquet, Alain Prost and Niki Lauda.

Nelson Piquet is highly praised by Gordon Murray (former Brabham designer), see statement reproduced below:

"I worked for years with drivers who had a lot of natural ability, but not so much technical or communication ability from the point of view of chassis setup. But Nelson was a really good mix: he had enormous natural ability, obviously, but also a great understanding of the technology that makes the car faster."

(Gordon Murray Source: https://projetomotor.com.br/gordon-murray-f1-piquet-senna-mclaren-brabham/)

Niki Lauda was considered a good tuner of cars since the 1970s, so much so that Clay Regazzoni recommended him to be a Ferrari driver in 1974. Lauda gave recommendations and saw problems in the car that other drivers did not see, and the Ferrari car made an absurd leap in quality from 1974 to 1977 with him on the team. In addition, in the 1980s, the Austrian became practically the mentor of drivers like Nelson Piquet and Alain Prost, who were naturally good tuners, but learned how to communicate with the engineers with the Austrian.

Alain Prost is highly praised by John Barnard (former McLaren and Ferrari designer), who worked with Lauda, Prost, and Piquet. See the interview below from the newspaper O Globo, April 25, 1993, p. 54.

These were the best car setters in the history of F1

There were other drivers who were also considered good car setters by the engineers, they are:

-

Fangio

-

Brabham

-

Graham Hill

-

Stewart

-

Fittipaldi

-

Senna

-

Schumacher

-

Moreno

-

Barrichello

-

Button

-

Sainz Jr

-

Max Verstappen

We should mention that there are "urban legends" that Senna and Schumacher were not good tuners, which is not true.

Senna was a good setter up, but not as good as Piquet, Prost, and Lauda, as he focused more on the engine and tires than the chassis. After working with Prost, he learned to tune the car's chassis and became a very good tuner, as reported by McLaren engineers and Ron Dennis himself.

Schumacher was also a good tuner, but he struggled with understeering cars (front), so he always preferred oversteering (rear). When Rubens Barrichello joined Ferrari in 2000, the Brazilian helped the German with other better setup options, and this significantly improved Schumacher's performance and helped him win five titles with Ferrari. But none of this diminishes the German's ability to tune cars.

Stewart and Fittipaldi were also good car setup specialists: the Scotsman was one of those responsible for Tyrrell's rise in 1971, 1972, and 1973. Fittipaldi, on the other hand, was known for passing on good information at Lotus and was nicknamed "velvet bum," so much so that when he left the English team, the team completely lost its way in F1. In contrast, in 1974 and 1975, the McLaren team grew with the arrival of Emerson, and team boss Teddy Mayer himself acknowledged this at the time.

James Hunt, champion with McLaren in 1976, also acknowledged: "I owe a lot to Emerson's work at the end of '75 with the McLaren 23." (Anuário Motores 77 pg 100)